Before the tragedy of his death at 34, his reputation had become firm, not only in Europe but in the United States as well. His influence survives among many young artists.

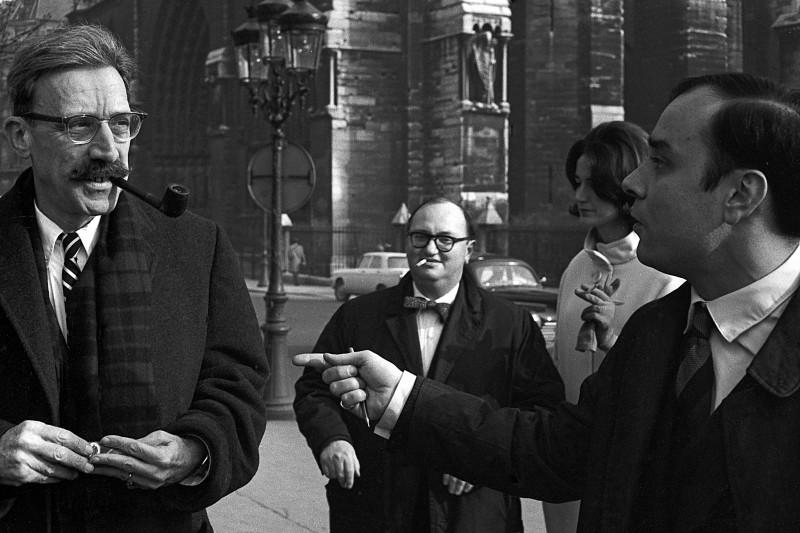

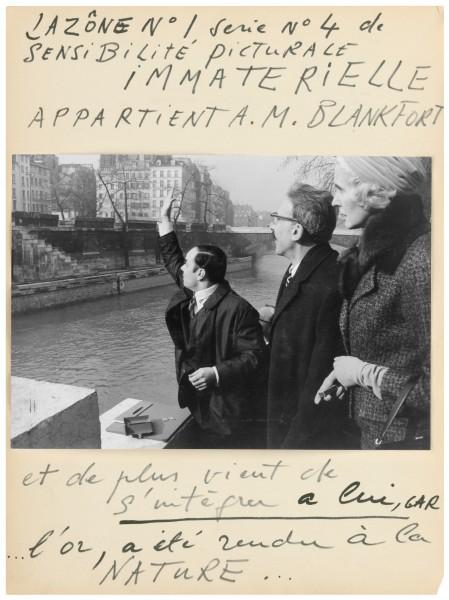

I had heard about Klein’s “immaterials” from another collector, Virginia Dwan, at whose gallery in Los Angeles I had first met Yves Klein and Rotraut, his German-born wife. Thus, when I agreed to buy one, I had some inkling, but not more, of what one did. First, I had to buy 160 grams of pure gold in sixteen ingots. Then it was arranged for us to meet at the Seine near the Pont Neuf at eleven o’clock in the morning. It was February 2, 1962. When my wife and I arrived, we found Yves, his wife, and several witnesses, among them François Mathey of the Louvre, Madame Bordeaux Le Pecq of the Musée d’Art Moderne, Virginia Dwan, and Pierre Descargues, the critic. Klein directed me to take half the ingots from the box which held them. I was tense; my body, taut. The eight ingots seemed very heavy in my hand. I looked at Klein; his face was young and his neatly combed hair was only slightly touched by the breeze. His eyes left mine and were studying the river and the sky. Next to me was my wife, wearing a grey velvet turban and a fur scarf around her neck. The sun was bright and the day was not as cold as it ought to have been for February. “Now,” Klein said in a low voice, “throw the gold pieces into the river.” At this point, I’m not sure how long I hesitated. The act of literally throwing money away was not consonant with either my upbringing or my character. Nevertheless, I felt a wave of exaltation and with it a kind of creativity which I had experienced before only a few times while writing. It was a sensation of being outside my body, not completely myself; a paradox of taking in more than I gave out. Slowly, my hand lifted itself high in order to reach the Seine some yards away, and in a surge of ecstasy I threw the gold pieces toward the river. I followed the course of their rise, shining in the sun and then disappearing with modest splashes in the water. I felt purged; it was as if I had flown with them, leaving behind the baggage of daily living. I was recalled by the sound of Klein’s words which I couldn’t make out. He handed me a sheet of paper and asked me to read it. It was the bill of sale.

“What do you want to do with it?” he asked. My impulse was to fold it and put it away, but a look of intense expectancy in Klein’s eyes held me back. “Since this is an ‘immaterial,’” I murmured, “Let’s keep it that way.” I fumbled in my pocket for a match. Before I could light one, he had one of his own lit and handed it to me. I laid it against one corner of the sheet of paper. Silently, we all watched the contract turn to ash, and as it floated up, Klein pushed it toward the river. That seemed part of the ritual. The ashes disappeared, and for a moment we were silent. The Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensitivity, as Klein called the event, was mine as long as I live.

I must add that I’ve had no other experience in art equal to the depth of feeling of this one. It evoked in me a shock of self-recognition and an explosion of awareness of time and space.

Michael Blankfort