A privileged few, friends and art critics, were invited to the first floor of the Colette Allendy gallery to see the ‘Surfaces et blocs de sensibilité picturale’ (Surfaces and blocks of pictorial sensibility) presented in an apparently empty room. An article in the magazine Cimaises (July-August 1957) and a film attest to the reality of this experiment. The film, silent but in colour, takes us on a subjective camera tour of the exhibition, from the entrance to the gallery, through the ground floor, to the first floor. There, the artist himself awaits us. His gestures and attitudes invite us to look at invisible ‘Pictorial Intentions’ hanging on the wall, and to consider carefully ‘Blocks of Pictorial Sensibility’. None of this can be seen, of course, but does that mean there is nothing there? Reality cannot be reduced to visible realities alone. Yves Klein believes that the essential quality of painting lies in the ‘pictorial sensibility’ that emanates from the painting. We all feel its presence, without being able to say where it is or how it affects us. It was this invisible essence of painting that he set out to present directly, without intermediaries, without the medium of the painting.

The confidential attempt made in 1957 encouraged Klein to continue along this path. He meticulously prepared the exhibition that has since become one of the most famous of the twentieth century, under a name that does not make it easy to understand what was at stake: ‘Exposition du vide’. The day chosen for the opening, 28 April 1958, a major artistic and social event, coincided with the artist's thirtieth birthday. Once again, he knew how to find the right formal means to convey his intentions when he ‘decided to present “Immaterial Blue” at Iris Clert’.

Klein organised a kind of diptych. The invitation card featured a text by Pierre Restany, printed in blue. On each envelope, the blue stamp, a miniature monochrome, recalled the blue era on which this event was based. The obelisk on the Place de la Concorde was to have been illuminated in blue on the evening of the opening, but the Paris Prefecture of Police withdrew its authorisation at the last minute. With Iris Clert's agreement, the artist closed the door to the gallery on the street and painted the window in blue up to a certain height, so that it would be impossible to see the contents from the outside. A large blue canopy surrounds the entrance to the building, through which visitors must pass before entering the gallery, whose service entrance is concealed as well as marked by a blue tapestry. Before entering the exhibition, visitors are offered a blue cocktail. The blue visible on the outside will also be present inside them. When they finally arrive inside the gallery, they discover an empty room, freshly painted white, including the inside of the display case, which is blue on the outside. So, as Klein explained on several occasions, the ‘tangible and visible Blue’ is present everywhere in this exhibition, but exclusively outside the gallery, which hosts the ‘immaterialisation of Blue’, offering a setting for the ‘coloured space that cannot be seen, but in which we immerse ourselves’.

Should we look at these white-painted walls? Should we consider the ‘void’ itself, presented here with a certain emphasis? Or, more subtly, the exhibition of the White Cube as such? No, of course not, because in the gallery reigned ‘the true blue, the blue of the blue depth of space. The blue of [his] kingdom... of our kingdom! If we follow the artist's explanations, whether we agree with them or not, we have to admit that the gallery space, far from being ‘empty’, was saturated with ‘pictorial sensibility in its purest state’. All that remained of the painting, physically absent but emotionally present, was its essential quality, a ‘radiance’ that is not visible - which is not to say that it cannot be ‘perceived’. Ephemeral by definition, the exhibition remains inscribed in our memories, and its memory is perpetuated through documents, accounts and analyses.

When he was invited to take part in a group exhibition organised in Antwerp, Vision in Motion/Motion in vision, Klein was not yet looking to perpetuate his ‘immaterial pictorial sensibility’ for collectors and posterity. He decided to take part in the event and to show nothing, or at least nothing tangible. On the opening day (17 March 1959), when the space reserved for his works remained ‘empty’, he told the organisers and the public: ‘First, there is nothing, then there is a deep nothing, then a blue depth’ - a phrase borrowed from Gaston Bachelard's L'Air et les songes. One of the exhibition organisers asked him where his work was located. ‘There, where I'm speaking at the moment’, says the artist. ‘And how much does it cost?’ continued the questioner, to which Yves Klein replied, sovereignly: ’One kilo of gold, one kilo of pure gold ingot will be enough for me’.

In the absence of any identifiable concrete preparation, the verb alone, uttered by an authorised speaker, can make the work appear to the minds of the assembled spectators. Here, Yves le Monochrome guarantees the effective presence of an invisible sensibility. To introduce immaterial works to an art market that confers symbolic recognition, the artist develops receipts in counterfoil notebooks. He also laid down ‘ritual rules’ governing the transaction, designed to avoid any confusion between the work itself, which was immaterial, and the receipt given to the buyer. The ‘zones of immaterial pictorial sensitivity’ are grouped into seven series, each worth between 20 and 1,280 grams of gold. Of course, buyers can keep their receipts, but they are warned that in this case, even though they are the owners of the zone acquired, ‘all the authentic immaterial value of the work’ escapes them. To ensure that the ‘fundamental value of the area belongs to him once and for all’, he must ‘solemnly burn his receipt’. So there was no trace of him, apart from his name on the counterfoil of a notebook, and the memory was inscribed in his memory as well as in that of the witnesses required for the ceremonial transfer. Moreover, as the rule unambiguously stated, while the purchaser was burning his receipt Klein had to dispose of half the gold received in payment for the area in question in a place where no one could recover it. Shortly before his sudden death, he performed this rite three times, in the shadow of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, on the banks of the Seine, where he threw the gold away. His friend Claude Pascal, Dino Buzzati and an American screenwriter, Michael Blankfort, burnt their receipts on this occasion.

The so-called ‘The Void’ exhibition, the use of an initiating word in Antwerp and the sale of ‘zones of immaterial pictorial sensitivity’ allowed Yves Klein to proclaim: ‘It is not enough to say or write: “I have overcome the problem of art”. You still have to have done it. I have done it. These three sentences head the pamphlet he published in December 1959, Le Dépassement de la problématique de l'art. Here the artist revisits various texts, takes stock of some of his achievements, and mentions several projects, in particular the ‘architectures of the air’ on which he is working with Werner Ruhnau, and the ‘Creation of a centre of sensitivity’, a new kind of art school whose model seems to have been prophetic when we consider the evolution of fine art schools. The April 1958 exhibition, which he gives a precise yet enigmatic title in the book, ‘La spécialisation de la sensibilité à l'état matière première en sensibilité picturale stabilisée’ (‘The specialisation of sensibility in its raw material state into stabilised pictorial sensibility’), is explained with consummate pedagogical skill. Klein was never content to simply do things; he was keen to make them known and, even more so, to make them understood’.

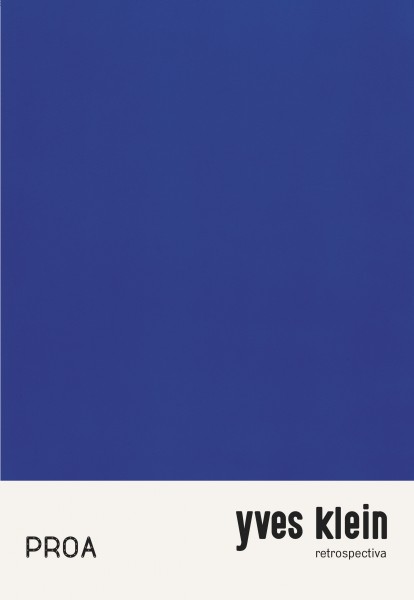

Denys Riout, excerpt from " Des cendres incandescentes", catalogue of the exhibition "Yves Klein - Retrospectiva", PROA Fundación, 2017