He walks the tightrope of the sublime", said Dominique de Ménil in the catalogue for the exhibition held at the Centre Pompidou in 1983. If by the sublime we mean a predisposition to a mysticism embodied in his life and his works, then Yves Klein was indeed always close to it. But, as always with the artist, ambivalence is the order of the day. The forms of spirituality that nourished him were extremely diverse, even contradictory in their principles. While the search for elevation and purity guides his art, it is above all the result of a very personal synthesis of these different influences.

THE INVISIBLE AS A SOURCE OF PURE ENERGY

The Klein system is above all an ambiguous relationship with God. The tangible revelation of the divine appeared to him as a child during long masses dedicated to Saint Rita. The splendour of Catholic worship delighted him at an age marked by a desire for transcendence that was all the more ardent because his parents professed an amused distance from faith. As he left adolescence, Klein dreamt of travelling, of escaping. And above all to escape a French society that seemed so narrow to him.

In 1947, in Nice, his quest for something different led him to discover judo at a club where he met Claude Pascal and the future Arman. Combining physical mastery and mental elevation, this sport fascinated him. He devoted himself totally and intensely to it. Above all, judo opened other doors for him, that of a renewed perception of the world, that of a form of asceticism freed from the weight of Western history.

Klein and his friends discovered this same distance from the conventions of society in Max Heindel's Cosmogonie des Rose-Croix (1909). The work seems to resonate with judo philosophy: life, i.e. pure spirit, is opposed to form, dependent on a limited physical world. Klein was enthusiastic about the promise that human beings could transcend material limitations. For three years, he took correspondence courses and became fascinated by the theosophical theories that suggested the possibility of levitating or gaining direct knowledge of the world without recourse to the necessarily imperfect senses.

The immaterial gradually took shape in his mind. However, it took him a long journey to perfect his judo in Japan to refine this relationship with the invisible as a source of pure energy. Zen and Shinto principles also freed him from Rosicrucian theosophy, which he later judged to be akin to occultism. But the fascination remained. On 11 March 1956, he joined the Order of the Archers of Saint Sebastian - with the motto "for colour, against line and drawing" - as much to do with his desire to belong to an "occult" order as with the possibility of parading around in the grand costume of a member.

FROM MONOCHROME TO VOID

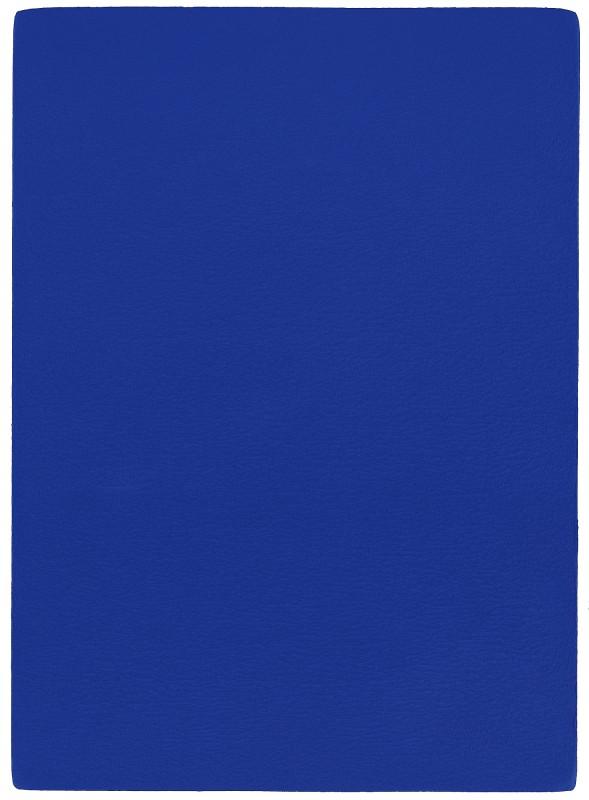

These different influences led him to produce his first monochromes in 1955. Although at first he used them to assert that he was beyond abstraction, the monochrome soon became the emblem of a "diffusion of energy in space, its fixation by pure colour and its impregnation on the sensibility", as he told the critic Pierre Restany in 1956. The dazzle of colour (including the famous IKB, International Klein Blue) soon led to a materiality that was too visible, too present. Going beyond the problems of art meant giving his practice - notably the Monochromes and the Impregnated Sponge Sculptures (1959) - a spiritual and transcendental dimension never before approached by any other artist. He sought to immaterialise his ultramarine blue and gave his system of thought messianic overtones. To paint is not to apply colour, but to fix on a support "the pictorial moment born of an illumination through the impregnation of life itself". While such words may seem hermetic, they above all confirm an artist who imagines himself as a ferryman, a veritable 'medium' capturing 'pœ́tic events' and condensing them onto a medium.

Unlike the Surrealists, who tried to give form to the impulses of the unconscious, or the Abstract Expressionists, who transformed the artist into the hero of a liberated gesturality, Klein sought to capture the radiance of life and nature. His practice consisted of imbuing a work of art, or even a space, with this radiance. The "Emptiness" exhibition (28 April 1958) at Iris Clert can be seen as the culmination of this research. Although the showcase was painted blue, and visitors were prepared with a ceremonial display of Republican guards and a blue cocktail on entering, the space inside was a white void devoid of any works whatsoever. However, Klein insists that he had previously psychically saturated it with a "pictorial state" and an energy that, although invisible, was totally manifest to him. At group exhibitions, notably "Vision in motion / Motion in vision" (Antwerp, March 1959), he renewed his posture, leaving the space reserved for him empty, or more precisely charged with a "pictorial sensibility". These proposals were all accompanied by texts, publications and interviews attempting to justify this advance of art into the invisible. These often nebulous statements blur the perception of his intentions by the French art world, which is resolutely hostile to his ideas.

VISIBLE, TANGIBLE, TRANSFERABLE?

For the art market, a work is first and foremost something that can be sold, whether visible or not. This raises the daunting question of how to sell an immaterial work of art, and under what conditions. Gold, a highly symbolic metal, becomes the currency of exchange, duly attested by a 'receipt'. Klein recycled this gold, sometimes throwing it into the Seine to buy a Zone de sensibilité picturale immatérielle (January 1962), before incorporating it into his works. It became increasingly present in his later works, such as a series of monochrome triptychs combining blue, pink and gold (1960) and the Ex-voto dedicated to Saint Rita of Cascia (1961). Even if the artist does not allude to it directly, gold is also a distant reference to the art of the icon, where a plain background made of the most precious metal signified the impossibility of representing God. His portrait reliefs of 1962, particularly those of Arman, can be seen as secular equivalents of the transcendence once induced by the icon. Accepting paradoxes, Klein likes to muddy the waters.

Shortly before 1960, Klein was faced with another dilemma. The validity of the "disembodied space of immaterial blue" as an artistic proposition - in other words, the void - could only find its relevance in relation to other, tangible, achievements. The Anthropometries (1958) and then the Peintures de feu (1961) were one possible response. The former had the function of reintroducing the body - the Christian body, the bearer of a possible incarnation - into his work. Nude women coated in paint left the blue imprint of their flesh on various supports, guided by an artist in a dinner jacket who was transformed into the great organiser of these public sessions (February and March 1960). Although Restany considered these models to be living paintbrushes, the young nude women were in fact given a great deal of freedom of action, far from any hint of slavish subjugation. Anthropometry thus becomes the sensitive trace of an imprint 'torn' from the body, a kind of sublimation of the flesh. It is thus fully in keeping with a spiritual approach: the creation of a two-way passage between the visible and the invisible. As for the Peintures du feu (Fire Paintings), mainly produced between 1960 and 1962, they encapsulate the power of a spiritual energy that, as in judo, is suddenly released through the dazzling gestures of the artist wielding a powerful burner. With Le Saut dans le vide, a prophetic image of his death on 6 June 1962 at the age of thirty-four, Klein reintroduced the marvellous into his work, but a marvellous that suddenly brought the divine back into the realm of the sensible.

extract from the special edition "Yves Klein Intime", published by Connaissance des arts to coincide with the exhibition at the Hôtel de Caumont in Aix-en-Provence in 2022.