Never using the line, one has been able to create in painting a fourth, fifth, or whatever other dimension – only color can attempt to succeed in this exploit. The monochrome is the only physical way of painting – permitting us to attain the spiritual absolute. If we imagine that cinema always existed, that one only knew moving pictures, then the creator of a fixed image would today have been considered a genius!

Young painters such as Alberto BURRI, TAPIÈS, MACK, DAWING, JONESCO, PIENE, MANZONI, MUBIN and others still that I do not know have now come to paint in an almost monochrome manner. But this is not a grave matter for me, quite to the contrary. It is not important who first composed a monochrome painting.

MALEVICH, by a path different from my own, which is that of the exasperation of form, almost arrived at the monochrome forty years before me, although that may never have been his intention (his white square on white background hangs in a New York museum).

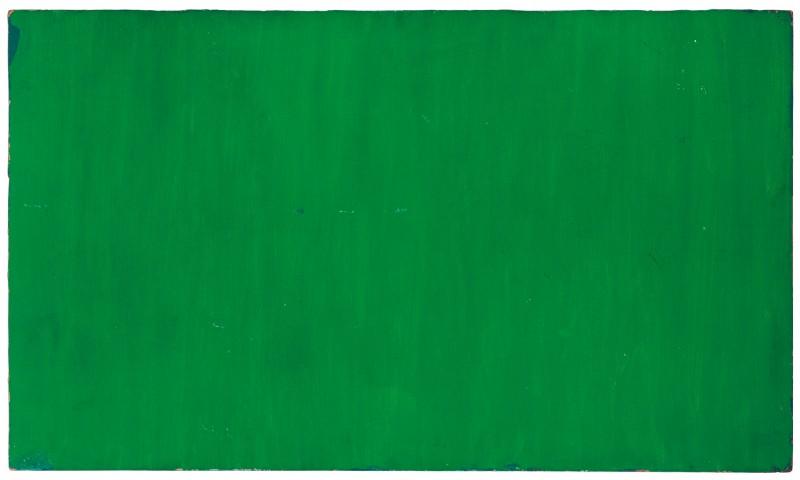

A Polish painter, disciple of MALEVICH, has painted monochromes with a compositions of forms in relief in the style referred to as unist. All of that is unimportant. It is the fundamental idea that counts, through the centuries. I consider GIOTTO as the real precursor of the monochrome painting that I practice, for his blue monochromes in Assisi (called decoupages of the sky by art historians, but they are clearly unified monochrome frescoes) and the prehistoric men who entirely painted the interiors of their caves in cobalt blue. And then there are the writings of monochrome thoughts by painters such as VAN GOGH, DELACROIX. I consider myself on the lyric side of painting.

These exasperated with form, the Polish unists, the suprematists and the neoplasticians still live in the visual, in the academic side of painting. I will expand somewhat on this, for it seems important to me to take stock (provisionally anyway):

In June 1957 I exhibited in LONDON and had occasion to meet with an attaché of the Soviet Embassy and speak with him at length about the case of MALEVICH.

He related to me how, some time after the October Revolution, MALEVICH and several of his students or followers organized a large exhibition in Moscow; certain among his disciples even exhibited, it appears, completely unified rectangular or square surfaces, white, black, color, but all clearly with the intention to reduce painting to form-phenomena and non-colors. In a manifesto, apparently out of print or lost, MALEVICH and his colleagues declared on that occasion that they thought to have reached the limits of painting and that, in consequence, they returned now to the collective.

They would, in effect, go off separately and work in factories or in the fields of collective farms after the close of the exhibition.

This story, true or false, is distressing for it shows whereto honest men are lead by academic obscurantism, which is to say, fear …

The line and its consequences – contours, forms, composition, etc. – had diverted these impassioned seekers into an impasse through the power of suggestion of an ephemeral reality: dialectic materialism. They abandoned poetry and sensibility at the junction of eternal life and fate, where they should have turned, had they been true painters, toward the absolute affective pictorial power of color. Thus reaching the exasperation with form without the immaterial and spiritual hope that color gives, it was entirely natural for them to give up art and to join their comrades of the great communist social experiment, which is also entirely in the same spirit: the exasperation with dialectical materialism and commonplace solidly tangible realism. Soviet Communism is also clearly an exasperation with form in regard to the social structure in opposition to Christian societies and the illuminated civilizations of the Middle Ages. Hence communism unifies and monochromizes, but it does so by killing the individual, the soul, while the Christian democracy tries to stimulate the individual, albeit by precisely defining the personality and leading it to a concept of collective unity through its emotional foundation and not through its material heritage.

I allow myself here to call to mind that, in my paintings, I have always sought to preserve each grain of powder pigment that dazzled me in the radiance of its natural state from any alteration whatsoever by mixing it with a fixative. Oil kills the brilliance of the pure pigment; my fixative does not kill it or anyway much less so.

I see its origin in the dispute between INGRES and DELA-CROIX. On the side of INGRES: a line of academics terrorized by space who take refuge in the false and temporal vanity of the line, the traditional symbol of the inhuman (Ingres said: Color is only the lady-in-waiting15), which culminates, after passing through realism (Courbet), in the cubists (in a theoretical sense, excluding the exceptional cases of painters who are painters in spite of themselves, in spite of their attachment to working in accordance with a theory), in Dada, the neoplasticians, the unists and all the so-called cold or geometric abstract artists. MALEVICH arrived from there, the pinnacle of the exasperation with form.

While, following DELACROIX, one arrives at our own time by way of lyricism, the impressionists, the pointillists, the fauves, by way of a certain affective surrealism, lyric abstraction, right up to the monochrome that I practice and which is not at all monoform, but which is, through the color, the pursuit of every sensibility for the immaterial in art.

I shall here cite the following passage from Air and Dreams by G. BACHELARD: Some will no doubt object that I am making too much of a very restricted image. They may also claim that my desire to think through images could easily be satisfied by the flight of a bird which is also completely carried away by its élan and which is also master of its own flight path. But are these winged lines in the blue sky really anything more to us than a chalk line on a blackboard whose abstraction is so often criticized? From my particular point of view, they bear the mark of their own inadequacy: they are visual, they are drawn, simply drawn. They are not lived as acts of will. No matter where we look, there is really nothing but oneiric flight that allows us to define ourselves, in our whole being, as mobile, as a mobility that is conscious of its unity, experiencing complete and total mobility from within.

At the Biennial Exposition in Venice in September 1958 I questioned a Soviet art critic on MALEVICH to verify the value of what the Russian diplomat had one year earlier communicated to me in London. His response was somewhat different. He told me that MALEVlCH, after that famous group exhibition, had begun to paint in a realist-trompe-l’oeil manner (and had continued to do so until his death, around ten years later), becoming stylish, etc., and that is where the visual and the exasperation with form leads to when one strays from the real value of painting: color. It leads to the miserable trompe-l’oeil.

The integrity of MALEVICH is above reproach. One cannot presume upon such a man, whom I deeply respect for his absolute commitment (because, for me, he is a painter despite himself, as I have already said) and it is herein that it becomes dramatic: that he was constrained by the regime to go there. KANDINSKY left Russia after the October Revolution to work freely. MALEVICH, too, would certainly have been a man to leave Russia if he had felt ill at ease to continue to paint and evolve in his own way. In fact, he had affectively attained not the limits of painting but the limits of his art, the limits of his own art, which, already, was no longer (in reality) painting after he abandoned the illumination of total freedom through color.