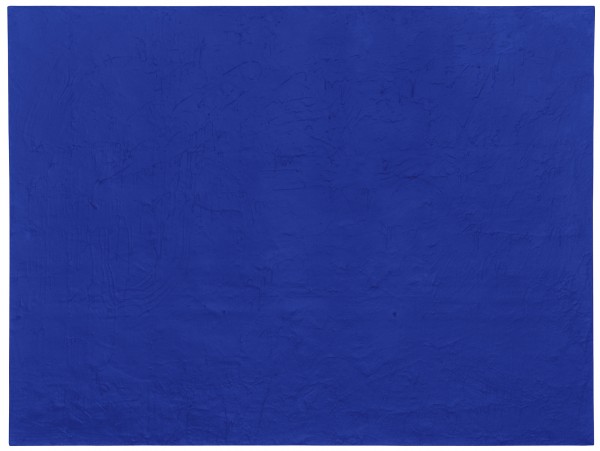

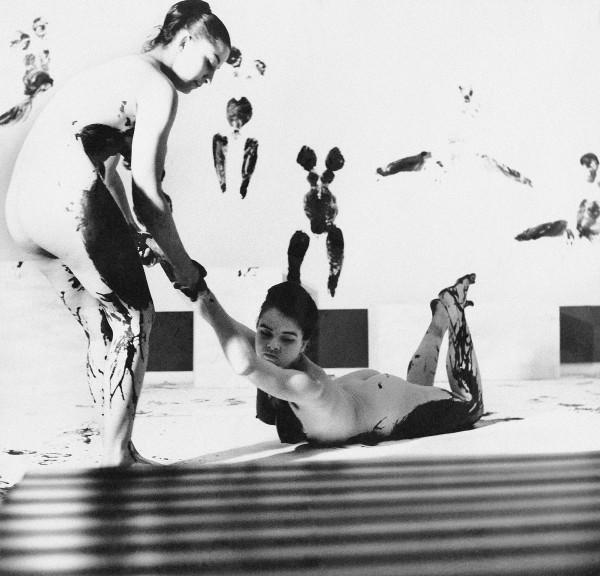

Having immaterialised blue, having gone beyond the problem of art, can we go any further? Probably not, but going elsewhere is certainly possible. And that's exactly what Klein did. Alongside the monochrome/immaterial pictorial sensibility axis, he never stopped exploring other paths, conquering hitherto unknown domains and inventing possible territories. At the very moment when he deprived the monochrome painting of matter, he gave painting an unexpected physicality. On 5 June 1958, shortly after the closing of the “Void” exhibition, he organised a singular painting session at the home of a friend, Robert Godet. In front of the guests gathered in the flat, a naked young woman, smeared with blue paint, crawled across a support laid out on the floor, transforming it into a monochrome surface. Klein had just given his first public demonstration with a ‘living brush’ at work. How better to affirm that painting, made up of colour(s), is always also the result of the action of a body?

Gestural, expressionist or lyrical abstract painters, depending on the name and the country, were triumphant at the time. Jackson Pollock and Georges Mathieu involved their own bodies in spectacular fashion. Klein always fought against the idea he had of their work, saying for example:

"Abstract painting is picturesque literature about psychological states. It's poor. I'm glad I'm not an abstract painter."

To combat this ‘exasperation of the self’, he quickly adopted rollers to produce his monochromes. These painting tools can create different textures, depending on their material and design. More importantly for Klein, they imposed the “distance” of anonymity between the canvas and the artist, who was delighted with this: "My personal psychology does not permeate the painting when I paint with a roller. Only the value of the colour itself shines through in pure, clean quality. With a brush that is ‘alive and remote-controlled’, he retains control of the situation without having to intervene on the support himself.

This new procedure would be of little interest if the result were always a simple monochrome panel, as was the case at the private session organised at Robert Godet's house. This way of painting can only be fully effective if the viewer can easily trace the visual result back to its genesis, to the painting itself. To achieve this, the prints of the body must remain legible. Klein developed a suitable device and, when he was satisfied with it, invited Pierre Restany to come and see it in his studio. Udo Kulterman, director of the Leverkusen museum, was also present when a model was smeared with blue paint on her bust, stomach and thighs. On several occasions, the young woman placed her body on paper laid out on the floor or stapled to the wall. Restany was enthusiastic about the traces she left behind and, in his own words, exclaimed: "These are the anthropometries of the blue period.

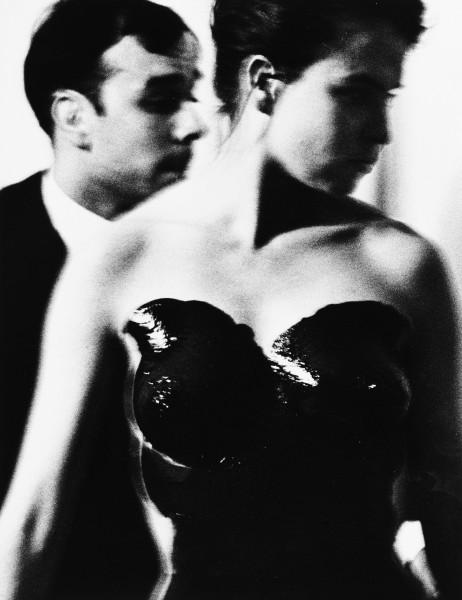

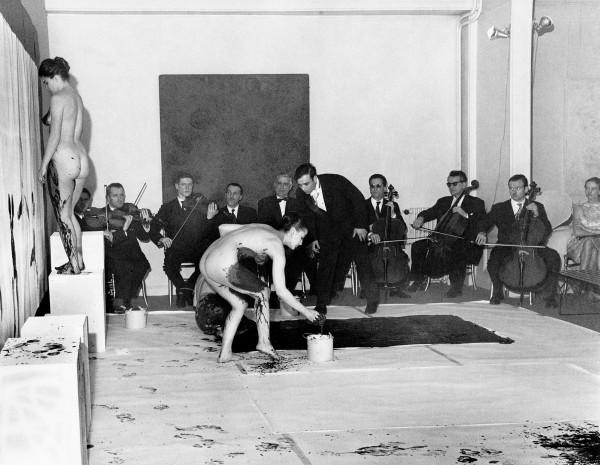

To publicise this innovation, which goes back to the dawn of time since our distant ancestors left handprints in caves, Klein presented a demonstration of anthropometry at the Galerie internationale d'art contemporain (Paris). The artist summoned the models, organised a dress rehearsal on site, invited musicians, photographers and a cameraman. Around a hundred people were invited to the ceremony (9 March 1960). At 10pm, Klein, wearing a black dinner jacket, white bow tie and the Maltese cross of the Knights of the Order of San Sebastian around his neck, his hands protected by immaculate gloves, made his entrance in front of the audience, followed by three naked young women carrying pots of paint in their hands. As they begin to paint their breasts, torsos, stomachs and thighs, the master of ceremonies, Klein himself, begins his monotone Symphony - performed here by three violinists, three choristers and three cellists. The young women then set to work under his direction. They carried out anthropometries on sheets prepared for the purpose. Once the pictorial work is finished, the models leave and the planned discussion can take place. It was during an exchange with Georges Mathieu that Klein made his famous remark:

"Art is health!"

The success of the evening is palpable in the grain of the film shot and the photographs taken that evening.

This “action-spectacle” makes manifest a major characteristic of Klein's art, the alternatives whose dual potentialities he develops simultaneously or in turn: colour and the invisible, the immaterial and the flesh, sound and silence. The monotone-silence Symphony, conceived by Klein and formalised with the collaboration of a more seasoned musician, Louis Saguer, consists of two parts. First, a continuous sound, with no variation in pitch or intensity, followed by an equal amount of silence. Performed that evening in public for the first time, it exemplifies the articulation of opposites. This is a major constant in Klein's essential creations, and means that lovers of the music need to understand each individual work in relation to others, as well as to the fundamental myths and beliefs of the Christian world - a world to which he fully belongs, as his devotion to Saint Rita, patron saint of hopeless causes, attests.

The performance of this bipartite symphony thus draws attention to two other diptychs: on the one hand, the visible, tangible blue and its immaterialisation staged two years earlier, and on the other, that of the invisible and the ‘flesh’, in other words the Incarnation. Here, blue makes a comeback without being carried by monochrome proposals, sponges or other works created by the artist. Colour is intimately associated with bodies in the splendour of their native nudity, bodies that are freed from any personal singularity to be better transcended within what Klein calls ‘flesh’, a term laden with Christian connotations. His pictorial work, both visible and invisible, does not deal directly with the Incarnation of Christ. But the return of the body evokes it without diversions. The whole theology of the icon, and then the whole Catholic tradition of images, is based on the dual nature of the Son of God made man, who became visible and therefore representable. The dogma of the Incarnation, an object of faith but also a cultural given, should not be considered as a subject to be dealt with head-on by the artist. It remains, however, the major conceptual horizon within which his creation is situated. This founding horizon enables us to understand the system of binary articulations that he uses to lead us to grasp the logic of the sequential sequences of an adventure that is perfectly coherent, despite the disparate forms to which it gives rise. It explores and deepens the antagonism between flesh and spirit, the sensible and the spiritual.

The legibility of the body prints, which Klein varied to his heart's content with the help of his models, reveals the carnal nature of anthropometry. They give the virginal blue the sensuality of contact and transform perishable flesh into a perennial trace. In this way, Klein revitalised the ancient tradition of the nude in painting. Photographic in their own way, since they record and fix an imprint, anthropometries represent bodies without resorting to representation. Indiscriminate, they attest to an absence. They also refer to a past presence, a temporality - as all photography does.

Denys Riout, extrait de " Des cendres incandescentes", catalogue de l'exposition "Yves Klein - Retrospectiva", à la PROA Fundación, 2017

First experience of "Living Brushes" at Robert Godet's apartment, 1958

Appartement de Robert Godet 9, rue Le-Regrattier, Île Saint-Louis, Paris, France

© The Estate of Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris

© Photo : All rights reserved

Appartement de Robert Godet 9, rue Le-Regrattier, Île Saint-Louis, Paris, France

© The Estate of Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris

© Photo : All rights reserved

![Score for Symphonie Monoton-silence [Monotone-silence Symphony]](/files/picture_thumbnail_871.jpg)