Following my exhibition Pictorial Sensibility in the First Mate- rial State [La sensibilité picturale à l’état matière première], or, al- ternatively, my Pneumatic Period, in April of 1958, Jean Tinguely, whom this manifestation of my work had genuinely impressed, proposed that we collaborate on the creation of a large mono- chrome painting. In one corner of it he would bring to life ele- ments of the same color to create, as he said, a phenomenon of metamorphosis in front of an apparent monochrome surface, which, however, was really pneumatic in the spiritual sense, that is to say, infinitely volumetrically abstract.

He promised to present this realization, signed by me as well as by him, to the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, of which he has been one of the pillars since its foundation, and from which I had been excluded since 1955, when I first tried to present a strictly monochrome painting. (See the account of that affair in the beginning of the book).

I enthusiastically accepted this proposition, and determined to go forward with it, we immediately purchased the particle board and the slats necessary for the fabrication of this collab- orative work.

Alas, the secretary of the Salon and then its very president cat- egorically refused acceptance of this work when Jean presented it to the Salon for registration – and Tinguely consequently resigned from the Salon without a moment’s hesitation. This incident only strengthened our determination to set off for the human adventure of creative collaboration, now more current than ever, which has been pursuit by some of the greatest con- temporary artists and architects since the celebrated pre-Hitler Bauhaus.

Extremely excited by this rejection, we decided to provoke, over a period of time, a protest against the Salon by exhibiting this painting, despite its rejection, in a Paris gallery during the Salon’s opening. Pierre Restany obliged to write a delirious and aggressive introduction. Jean Tinguely and I ought to attend the Salon’s opening reception and take possession of the event by projecting, with the help of blue flashlights, beams of blue on all the paintings and works exhibited while strolling among the crowd.

Nothing came of these plans, because, for my part, I was in full negotiations in Germany and could not take time off to take the evening train back to Paris only to return to Gelsenkirchen completely exhausted two days later. In short, the Salon of False New Realities narrowly escaped our protest.

Then came the holiday season, well deserved after a winter so charged with emotions and effort. We decided to take every- thing up again in September.

By September Jean and I had each deeply reflected upon the entire matter and our collaboration evolved towards a more in- telligent, more dissolved manifestation.

I remarked to Jean that the means of meeting each other in the Absolute, in great art, was not to create work separately and then naïvely superimpose two works to lure them into a col- laboration. Rather it was imperative that the work dissolve at the heart of the problem, static velocity, which is to say, velocity in place, and that I let it take form, a circle, in order that, by the velocity of the rotation, the monochrome surface become irides- cent and then visible again after the exhibition of my evolution towards the immaterial.

The color of immaterial blue, presented in April 1958 at the Iris Clert Gallery, had rendered the sum of myself inhuman, had excluded me from the world of tangible reality. I was outside of society, inhabiting space and no longer capable of returning to earth. Jean Tinguely perceived me in space and signaled to me by way of velocity a volumetric route of return to the ephemera of material life. It is this that I have called my rescue by Tinguely.

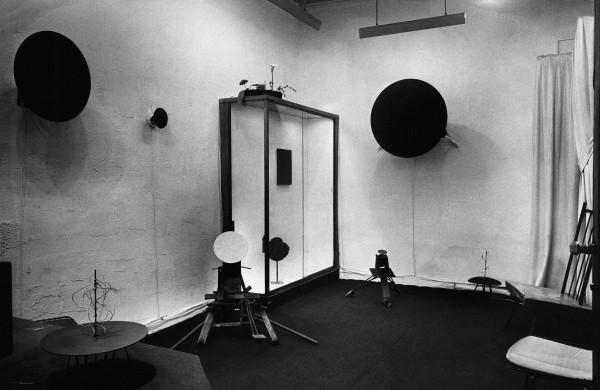

Pure Velocity and Monochrome Stability was a triumph of total and profound collaboration.

It was Solomon and Hiram Abiff who labored together on the construction of the temple.1 The Queen of Sheba, Iris, came to see the result and could only state that the work was beautiful and grandiose, but it was human only by its faults, by its errors. What were these faults and errors? The temptation to material- ize pure spirit! It is for this reason that Tinguely and I seek the means to continue after the exhibition of Pure Velocity and Mono- chrome Stability. Tinguely thus proposes to create a machine to produce monochromes. Being unenthusiastic about it, I pro- pose instead to Tinguely –to whom I had revealed that he was pure velocity – a new manifestation, more vast in spirit than our first collaboration. I propose to him that, by way of his truly pure velocity, he should enter into space and materialize, in the wake of his continual passage, the immaterial blue of my ter- ritory that he has continually traversed since our alliance. The abstract image has no picturesque, and ultimately, rustic qual- ity. Tinguely, the proprietor of velocity, enters my territory and launched himself into the air, which is presently the tangible aspect of all that belongs to me, and makes it circulate, and in the wake of this circulation, blue once again becomes visible.

Well, one day, I am holding a tube in my hand at Cassou’s hardware store; I hold it out like a revolver and amuse myself in thinking of it as a weapon; it takes in energy at one end and sends it back out through the other. Tinguely understands that quite well, and I then say to him: It would be great if air passes through it naturally for our exhibition.

This idea set forth, I take the problem up with him again that very evening, at La Coupole, I believe, and I draw a normal tube.

Tinguely draws a different tube.

I then draw this because I have always loved blunderbusses.

Then I explain to him how to circulate air inside the tube, in a utopian manner perhaps, but logical in theory. Heat one end and cool the other, a neutral region in the middle. Later, Wer- ner Ruhnau purports that it would suffice to heat one end only as that would create a temperature differential, which would make one end cooler in relation to the other. We go almost im- mediately to Hamburg with Ruhnau to study this with engineers at a large air-conditioner factory, and there everything takes precise shape.

Beforehand, Tinguely is dispirited and discouraged, I do not know why. Perhaps because I have not responded enthusiasti- cally to his idea of a monochrome-producing machine, he de- clared to me one evening, repeating this several times, even in the presence of Iris, No, this machine does not interest me; go ahead and produce it yourself. It’s a fine idea, but my heart is not in it.

And then, voilà! I return from Germany and I say my machine and everything changed; suddenly he becomes quite possessive of the idea!

The law of consequence, arising from all human attempts to materialize pure spirit, is passion!

Alas, passion always strikes Hiram but never Solomon, for Sol- omon attaches no importance to matter. He plays with it, he loves luxury, the superficial good life for all that is human, he doesn’t take the human condition seriously, whereas Hiram, on the con- trary, is a prisoner of the fatality of transformation – he is first human, then spirit. The Queen of Sheba loves the spiritual; she only allows for the necessity of temporary human condition – a psychological rivalry thus breaks out. Hiram withdraws into himself in anger (the wind of sensibility), jealousy is born, for the Queen of Sheba indicates her preference and honors passion over wisdom.2

I experienced this feeling in 1950 in Ireland, with Claude, when we collaborated in search of the truth.

The situation was now reversed for me. I was the brain, the creator, the physical man, and he was the spirit, the aristocrat, the creature of luxury – everyone preferred him to me, although I, too, was highly regarded. All the same, after a certain time, I was struck with jealousy. I was extremely unhappy and after months of suffering I quite understood that the point had to be made coldly, clearly, and dispassionately. Claude and I were at odds for six months because of that; now all is well – but what is certain is that once the point is made in me – from the mo- ment I have succeeded in brushing aside all the psychological justifications that I have built up within myself to strengthen my convictions against him, from the moment I have clearly seen myself to be jealous – I uprooted jealously by a violent act of spiritual purity, and then a terrible strength entered me and threw me into spiritual realism, the assured conqueror of all, and everything became possible for me – all the magical arts had no more secrets for me; I read and continued to read the memory of nature past and future, and astonishing possibilities of endlessly renewed discovery were at my disposal.

I wish this same destiny for Jean Tinguely who is a brother to me and who holds within himself great and pure talent. He must conquer his psychological personality and become an individual and anonymous creator who tells me, I, my, for all, be- cause all belongs to him, even that which is another’s, for noth- ing belongs to him, not even his own life. All of this is thus a game. One must live on earth in a man’s skin and in society as a pure spirit who has donned a costume and who plays a the- atrical role on a stage, sometimes one role, sometimes anoth- er, with the same ease – this is the luxury of the materialized pure spirit.

I had advised Tinguely, at the beginning of our collaboration, of the danger that he was running. I foresaw very clearly that there would come a moment when this stage would have to be passed over, that there would be nothing to do but to let it pass. As to myself, I have already crossed over; I know what it is, that it is hard.

It was on a Friday evening at La Coupole, in the presence of Iris, Tono and his wife, a Japanese sculptor, and Giovanella, when the crisis broke out in Jean at the moment I pronounced my machine to Tono, in speaking of our new creation in prepara- tion. It was not the my for which he reproached me; it was his own suffering that he howled out, and I, stupidly, was so blind as to become angry and to be hard on him. I deeply regret this. When I had directed a similar tantrum against Claude, but in fact against myself, he had been very generous and good to me. I know this now: he had said nothing; he had not become irri- tated and angry with me, where very easily he could have been, for at the time he was stronger than me, both physically and spiritually (his judo was then better than mine).

When one is stronger, one should be more charitable (in the profound meaning of the word, not in the idiotic and miserably vulgar official meaning).

It is for this reason that I write these lines, to recapture my gesture of anger directed against a man of good will who was suffering, caught up in the trap of passion. I should to have been full of good humor that evening and replied to Jean Tinguely: Be outrageously selfish; be as much an egotist and as egotistical as I am and become spiritually superior to me, then all the world will love you more than me and Iris will no longer call on you in my absence to declare to you, Ha! If Yves were here! Yves, the genius, the one and only true genius. Then it would be you who is the genius, the unique and the best genius, and then it would be me who would be- come jealous and envious and who would detest you – and it would be me who would find some futile reason to explode in anger and revolt against you.

That evening, what you told me that it was you who had invented the machine, that you had forbidden me to proceed without you, etc., it was as if we were aviators and you had said to me, Go Ahead! after having prepared everything and established all the rules for me, and then said Depart to me, the test pilot – then I, at last having taken off and alone in flight high above, I, would then have taken full control of the machine, for safety in flight then depended upon me than you! You, you remaining on the ground; I am the one who risks his neck if something does not work up there – which means that in flight, I think no longer of you; I think only of my machine.

You, below on the ground, you see that and you are very happy; everything is going well. When suddenly people come up to you and say: He’s an ace! This is fantastic! He is the only one to do that! He is a genius! – and you on earth are sick to you stomach, for it is thanks to you that everything functions, just as much thanks to you than to me.

Then, infuriated, you take a machine gun and shoot at me to bring me to down – and I, evidently, at first astonished, I come back to bomb and neutralize you – but a bombardment throws everyone down to earth, and it is in this that I am so very wrong. I was not wrong to say my machine, I was wrong to violently return fire.

This machine, my dear friend, belongs to you and to me, although this may not be quite what you told everybody at La Coupole. It was not you who conceived it, it was my idea, the tube, my idea even in the majority of the technical details; my memory is very clear at present; I can describe everything, point by point, regarding how it came to be – but it would be infantile to have to do this – for I attach no importance to it. All that I can say as to your participation in the conception of this machine is that it was my contact with you that inspired me to create infernal and amazing machines; it was under your influence, and this is most important for you, it seems to me, for you to have influenced me rather than to dispute over something as inexact as the paternity of this machine.

In any case, when you see me flying up there in a machine that we have created together and when you hear passers-by cover me with praise without acknowledging you – tell them that when I have re- turned and all is done, that I shall then declare that it is thanks to you that all of this has been possible. Which brings me back to my point, my dear Jean, which is to declare that one should not judge a col- laboration during its realization, but afterwards, when all has been accomplished.

Continuing with the example of aviation, if passers-by see you working on the machine that I have invented but you have produced, and I am not present, you should tell anyone who asks, This is my machine, and thereby all the praise will fall to you and nothing to me. Afterward, aloft, it is my machine – but in the end, when all is done, it is our machine.

| Technical | Tapuscrit et stylo sur papier |