DREAMS AND ILLUSIONS OF THE ORIENT

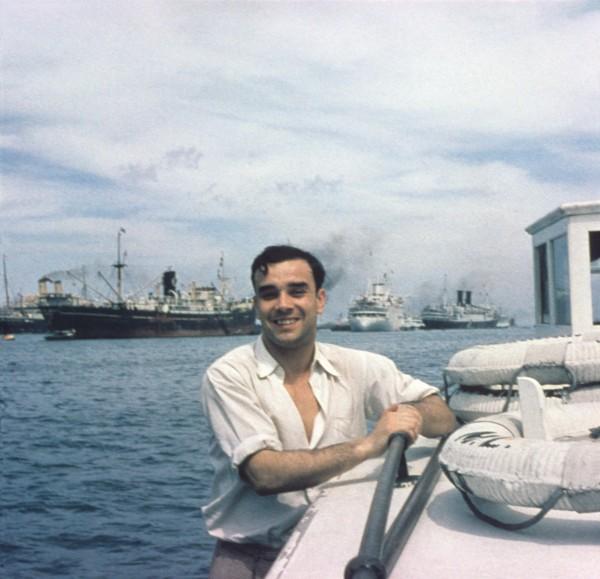

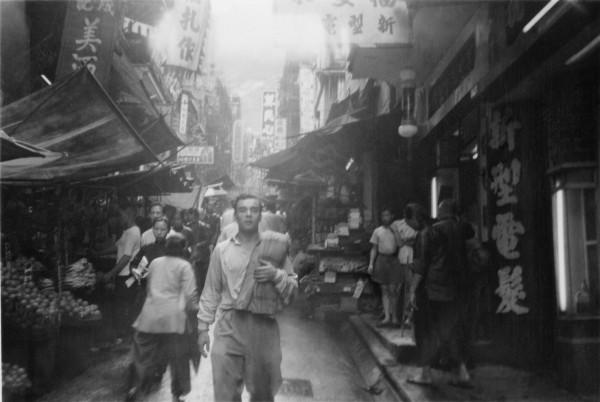

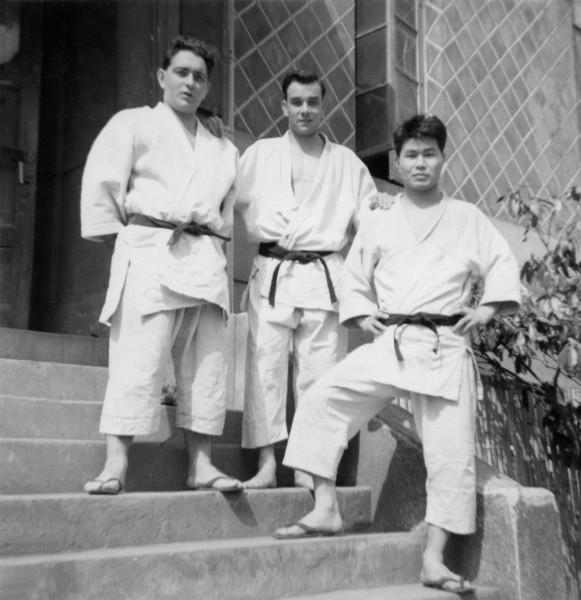

To learn judo at the Kodokan, the most renowned training centre in Japan, and come back wreathed in glory, possessed of unmatched competence – or nearly: such was the plan of this young man who was trying to find his way between two painter parents. His failure at the baccalauréat had closed the doors to merchant navy school and the prospect of travelling the world as an officer on ocean-going vessels. Enterprising and curious, Yves Klein had stayed in England and Ireland, in Germany and in Spain, had travelled in other European countries. With each stay, he began learning the country’s language. As he prepared to leave for Japan, he struggled over Japanese and its ideograms. In the diary he kept at the time, he wrote despairingly that “Japanese won’t sink in” (24 January 1952), and admitted that he was going through “a horrible period” (10 March 1952), then decided, no doubt provisionally, “to drop Japanese, to drop Spanish, etc.” He was worried, too: “I haven’t yet given up judo but I’m losing confidence” (10 March 1952). What remained was the dream of “going to Japan.” The journey, by boat, was itself an adventure. Going from one port of call to the next, the young man discovered new landscapes, customs, tastes, smells and sounds. This was quite a rare experience in those days. What did he actually bring back from his travels and his sojourn? This is difficult to gauge but it is obvious that such an adventure, at such an age, would have helped shape his personality and left its mark. His long stay in Japan certainly made a deep impression on Klein, who referred to it often, and it continues to compel all those who are interested, exasperated, fascinated or enchanted by his meteoric artistic career. Exegetes have often taken this experience of a culture so different from our own as a key to its explanation. The young Klein, they say, imported notions, concepts and ways of thinking from Japan, and these nourished and innervated essential parts of his protean production. And why not? I am therefore going to examine a few of the terms that are often evoked when connecting Klein’s art to his stay in Japan, inviting readers to draw their own conclusions about the validity of these links. Two pitfalls threaten to undermine the efforts of those who try to establish this inventory: the Charybdis of analogy and the Scylla of projection, or retrospection. A certain spirituality, a penchant for stripped-down forms, various declarations about the void, not to mention judo – these are a few bases to justify linkage with Far Eastern philosophies and practices, starting with the most popular, if not the best known of these, Zen Buddhism. As for retrospection, an insidious form of anachronism, it consists in understanding an earlier past in the light of what happened later, with the artist’s work and trajectory shedding light on certain events in his formative years. On this view, a conception of energy, of breath and of emptiness taken from Japanese culture (or Chinese, for emptiness – but no matter) would suffice to explain the untitled exhibition inaugurated at Galerie Iris Clert in April 1958.

ZEN

This term, this notion, this attitude towards the events and upsets of life – this presumed aesthetic, too – has enjoyed a popularity in the West reaching well beyond the philosophical-religious sphere in which it originated. Irrespective of its roots in Buddhist thought, the Zen school that emerged in Japan has become one of its emblems in Europe and in the United States, too. That is why the association between Klein, with his artistic mixture of sparseness and enigma and his learning of judo, and Zen, seems self-evident. Several of the artist’s friends and various writers have confirmed the validity of this spontaneous intuition by their personal recollections and writings. Arman, for example, remembers learning judo in Nice with his two mates at the time, Claude Pascal and Yves Klein: “As serious young people, we were at one as regards our attitude: we didn’t only want to learn judo as a sport and combat technique, we wanted to enter into the spirit of Bushido and therefore Buddhist Zen.” However, Yves Klein, who visited several temples, did not photograph any Zen gardens during his time in Japan and the word does not appear in his published writings. As for Arman’s recollection, it was formulated long after the event. Nevertheless, there were some in the 1950s who linked judo and Zen, notably Robert Godet. He published Tout le judo in 1952 and met Klein after he had come back from Japan. The relations between judo and Zen were indeed a pons asinorum, so much so that, in his preface to a book of recollections, Bernard Parizet approvingly noted: “Darcourt shows us that the Japanese masters are not sorcerers who gaze at their navel while meditating Zen but athletically toned champions, whatever their size or weight.” Now, this book is precisely about learning judo at the Kodokan, as the author experienced it in 1954 – that is to say, shortly after Klein’s departure. To multiply examples would serve no purpose. Sidra Stich reconciles different viewpoints when she passes on a fairly widespread opinion.6 Several of the artist’s friends did in effect observe that he “intuitively had a Zen spirit,” a spirit he had definitely not acquired from philosophical readings. It would follow that the Japanese sojourn gave shape to an affinity without, for all that, being a cause or an explanation. THE VOID The Void, a noun that Klein sometimes wrote with a capital letter, is now permanently associated with the name of this artist who created one of the most famous exhibitions of the 20th century, an exhibition known, precisely, by this name which is as spectacular as it is deceptive: “Exhibition of the Void.” Might he have imported from Japan this notion, which is central to Chinese art? It is very tempting to think so, and several authors have in effect stated or suggested as much. Nicolas Charlet explores the “fascination of the void, the guiding thread of Yves Klein’s life,”8 and develops the hypothesis of connections between the void, art and Oriental thought, Chinese art and judo. According to Ming Tiampo, it was a young critic he met in Tokyo, Segi Shin.ichi, who taught Klein “the concept of the void in Zen.” Annette Kahn, the artist’s biographer, is even bolder when she writes: “Yves dropped all his connections with Oceanside and the Rosicrucians and became fascinated by Shintoist thought, one of whose themes – in substance, ‘Everything begins with the Void’ – encapsulated, he felt, the whole mystery of the Universe.” It is true that, having become an artist, Klein did frequently evoke the void, but not once before that exhibition in April 1958. A little later, he nevertheless adopted the now common name, “exhibition of the void.” Then he imagined a progression in his work, a conquest by stages. He described this in a biographical note, “Yves Klein (‘the Monochrome’),” presenting himself as “the Founder of the ‘Monochrome,’ ‘Immaterial’ and ‘Void’ Movements.”11 In his texts and statements, the artist hardly ever linked this void to judo, and he never linked it to Far Eastern philosophies. Should this be taken to mean that the fact was so obvious that it was not necessary to emphasise it, or, on the contrary, was it confirmation that Klein came to the “void” by other paths?

THE KIAI

This notion linked to judo is explicitly taken up by Klein in a text titled “Réflexions sur le Judo, le Kiai, la Victoire constante” [Reflections on Judo, Kiai, Constant Victory]. Kiai, a cry that kills but also a cry of life and a cry that cures, arouses fantasies and is analysed in many books on judo. Robert Godet, for one, has a passage on this theme. What Klein says about it is notably different. Ming Tiampo defines it as “a technique whereby the judoka concentrates his spiritual energy (ki) so intensely that it liberates itself in the form of a cry.” Combined with the notion of energy, the term “spiritual” fits Klein’s art wonderfully well, and indeed he used the adjective “spiritual” often; it connects his practice of judo and his artistic career.

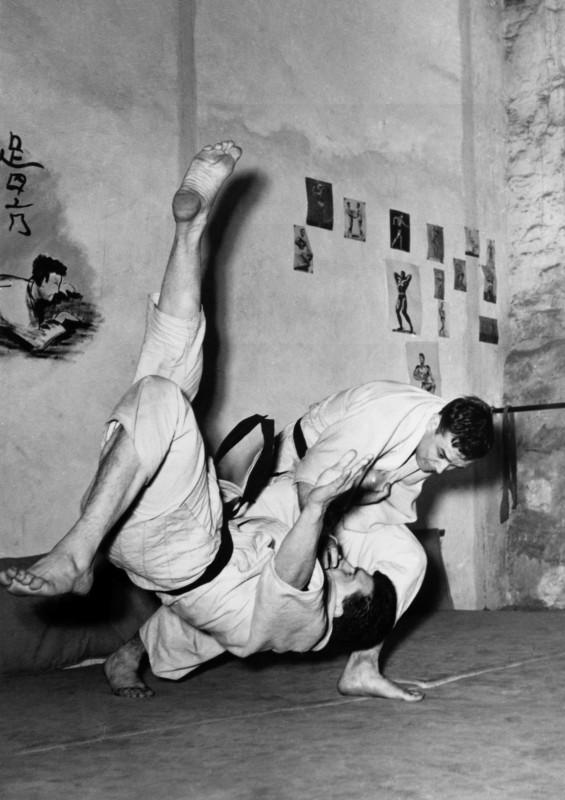

JUDO

Klein wanted to make judo his main activity, his profession. In a text that is thought to have been written in Japan, he praises it in the following terms: “Judo is art, it is an art of the same value as great music, for it must be recreated every time one wishes to play it again. It is a personal and universal art because it is art in combat, in other words, life itself.” But what role did the young man’s total commitment play in the elaboration of his art? His “Reflections on Judo, Kiai, Constant Victory,” mentioned above, begins as follows: “People often ask me if Judo has played a role in the conception of my pictorial work. So far, I have always answered no. But in fact, this is inexact: judo has given me a great deal. I started it at almost the same time as my painting. Both have lived with me as I live with my – physical – body!” On becoming a painter, Yves the Monochrome always, whatever the occasion, emphasised his rank as a 4th dan black belt. There was no boastfulness in this reminder, but on the contrary, a desire to make this singular capital clear to art lovers. The practice of judo structured his life and thought and his ethics and he transposed many of its principles into his artistic conduct. The text referred to above continues with this essential declaration, defining what he knows about judo: “First of all, an important principle: ‘have the spirit of victory.’” Klein needed to be moved by that “spirit of victory” in order to undertake what he dared to do in his work, and to succeed in it. Judo gave him that strength. It may also have been the cause of his early death. Here too, many authors have pointed out that the practice of judo was so tough, so strenuous, that many sportsmen took amphetamines, which were then freely available in Japan. It is thought that he may have continued taking them when he got back to Europe.

ART, ARTISTS, GUTAI

On his arrival in the port of Yokohama, Klein was met by connections of his parents and taken to an exhibition on which he commented unsparingly in his diary. He later met a number of other artists and organised two exhibitions of work by Marie Raymond and Fred Klein (Franco-Japanese Institute and Bridgestone Museum of Art, 1953). He brought back to France a collection of reproductions of Hiroshige prints (1797–1858) and a book of woodblocks by Munakata Shiko (1903–1975), in a style that was more popular than avant-gardist. They certainly had no influence on Klein’s artistic development; he was a judoka at the time. Later, a number of commentators could not resist making connections between Gutai and Klein.18 We should recall that this Japanese group was formed in August 1954, whereas Klein left the country in January 1954, and that its first public events date from 1955: the first issue of the journal Gutai came out in January that year, and the group had its first show as a group in Tokyo that March. Later, in 1957, the critic Michel Tapié met members of the Gutai group. He organised exhibitions of their works in the United States (1960) and in Italy (1961), but Klein only knew of them by hearsay, if that. During his time in Japan he asked the people he met to sign his diary. But, for all her eagerness to find Japanese resonances in the art of Yves the Monochrome, Ming Tiampo notes that “no one from the future Gutai group or anyone close to it appears there.”

IMPRINT, CALLIGRAPHY

Ever since the Neolithic era, the Japanese – like many other peoples, in fact – have explored the virtues of the imprint. Segi Shin.ichi speaks of “a very old and very popular technique in Japan: ink transfers.” A sheet of paper pressed against a fish that had been covered with India ink could capture and fix its general form as well as its scales and other details. “Now,” Segi continues, “the Japanese expression is gyotaku, pronounced ‘guio taku,’ with the word gyo meaning fish; the sound jyo means girl, young girl, and the expression becomes meaningless, but Klein laughed a great deal and perhaps that day he imagined a woman inked or covered with paint leaving a mark on a wall, on the ground, on a canvas.” The art critic seems more convincing when he recalls a film by Kamei Fumio that he saw with Klein in 1956. This film, Ikiteite yokatta (“a title that could have been translated as ‘The Shadow on the Stone’”), showed the negative trace of a man blasted by the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Now, one of the artist’s Anthropometries is titled, precisely, Hiroshima. There has also been speculation about calligraphy, particularly as the artist spoke about it several times and the subject was topical in the world of painting, with André Malraux declaring Georges Mathieu the first “Western calligrapher.” Klein’s long stay in Japan gave him legitimacy on subjects such as judo and calligraphy. Not unlike the Grand Tour undertaken by well-born young people in the 17th and 18th centuries, the journey made by the future artist produced an effect of authority that gave him the assurance he needed, a quality evident in his art and in his art-world interventions. The shock of disillusionment on his return, when the French judo federation refused to recognise the certificates he had obtained in Japan, was the decisive incentive. Now began his artistic saga, his “Monochrome Adventure,” which was an extension of his sojourn in “the country of [his] dreams.”

Denys Riout, excerpt of Yves Klein Japan, Editions Dilecta, 2020